Casperlabs Blog

Official Casperlabs blog

TPS Considered Harmful

by Onur Solmaz

In databases, a transaction is any operation on the state of the data store that preserves the consistency of the database. Database transactions are defined to be atomic, consistent, isolated and durable1, so that users don’t encounter anything inconsistent or unexpected. Transaction also has a more mainstream meaning in finance which probably inspired the usage in databases—the act of an exchange between a buyer and a seller. And more recently, transaction found use in cryptocurrencies, meaning any operation submitted by users that transfers coins (Bitcoin) or alters global state (Ethereum). Like database transactions, blockchain transactions are also ACID.

Transactions per second, or TPS, is a metric used to measure the performance of data stores. It is simply the number of atomic operations a data store can handle. TPS have been used to compare performances of different blockchains, and even blockchain performance to that of centralized payment processors. Although TPS gives us something to work with, I will argue that it is a bad metric for the reasons reasons below.

Variance

It takes computational resources to finalize a transaction, and their utilization varies greatly from transaction to transaction. This also reflects to the duration required to complete a transaction. If a user submits a bunch of transactions whose mean utilization of resources deviates from that of the network’s, they may observe a drastically different TPS than the one promised.

In Bitcoin, a transaction does not have to be between two addresses—it can have an arbitrary number of inputs and outputs2. This results in a discrepancy for those who assume a constant TPS for Bitcoin, because although block time has relatively low variance, number of transactions does not. For example, although blocks 492277 and 529245 have the same size (1000.012 kB), they have a 30x difference in the number of transactions (83 vs 2459).

Simply put, an object whose length varies a lot does not make a good unit of measurement. Since there is no “standard transaction”, we end up assuming an “average transaction” and use it in our benchmarks. But this also has its pitfalls.

Incomparability

Blockchains, and distributed systems in general, are designed for specific use cases, but one can generally find analogous operations among them. For example, Bitcoin’s main use case is sending coins and thus has a data structure (UTXO) that is optimized for it. Ethereum, on the other hand, targets generalized computing with EVM, and thus encodes transactions in a different way. Let’s see why comparing TPS across the two is problematic:

In Bitcoin, a 1MB block has roughly 2000 transactions on average, and average block time is 10 minutes. This puts the average transaction size around 1,000,000/2000=500 bytes, and TPS around 2000/600≈3.33 tx/s. On Ethereum, an ETH transfer costs 21k gas, block gas limit is currently 10m, and block time is 14 seconds on average. Thus, Ethereum’s throughput for ETH transfers are 10,000,000/21,000,14≈34 tx/s. But if we consider ERC20 tokens, an average transfer costs around 40k gas, and the number can get arbitrarily higher depending on the implementation. For example, transactions using the AZTEC protocol cost around 840k gas, which results in less than 1tx/s. Although AZTEC is a zero knowledge protocol which requires considerably more computation, token transfers that use it are still considered “transaction”s. This gives an idea why it’s not wise to liken an average Bitcoin transaction to an average Ethereum transaction.

Furthermore, networks that have the same functionality may end up having incomparable transaction specifications. Let’s assume we are comparing two smart contract platforms with different VMs, each having different sets of instructions. They are optimized for different types of computation and have a different utilization of resources. Thus, TPS itself is not enough to compare the performance of two protocols, even if they have the same use case. For an objective comparison, performance must be measured across other dimensions, including but not limited to encoding efficiency and computational efficiency.

Misdirection

Paying too much attention to TPS blinds us to the reason we have scaling problems in the first place: all networks are limited by bottlenecks. Most of the time, the problem is not the efficiency of the protocol’s design, but the efficiency of the infrastructure that hosts the network. When making marginal improvements to the infrastructure, bottlenecks arise for the resource which is the hardest to upgrade. For a global network, it is much easier for each miner to upgrade their own hardware, than to upgrade the entire physical layer of the internet. Thus, blockchains are bottlenecked by the global overall propagation delay, and that is the reason we can’t simply reduce block time or increase block size 100x for that much increase in performance.

As a system becomes more distributed, its dependence on communication between nodes increases drastically. Consensus bandwidth, defined as the maximum number of bits the network can reach consensus on, is the major bottleneck that prevents it from scaling. Then comes storage, because it requires an evergrowing continual allocation. Computing power is the least criticial, because it is consumed instantaneously and doesn’t continue to occupy hardware.

All Proof of Work blockchains eventually hit the bandwidth bottleneck—blocks become full, transaction fees skyrocket. Let’s look at the bandwidth of Bitcoin: 1 MB every 10 minutes yields 13.3 kbps. Clearly, this number is much lower than the speeds we are used to when connecting to the Internet. We must be able to afford at least the 56k of dial-up modems, right?

Wrong. This is not simply the speed of communication between two network nodes, but the throughput at which the whole network reaches consensus. For the whole network to reach consensus on a block, it needs to be propagated to a high enough portion of the network. If a block isn’t propagated to enough miners, the chain would fork when the miners who didn’t receive it mine a new block. A high rate of forking would result in a decreased quality of consensus and inefficiencies such as wasted energy.

In the paper Information Propagation in the Bitcoin Network, Decker and Wattenhofer derive the relationship between propagation delay and forking rate. The probability of forking is calculated by

where $P_b\approx 1/\text{block_time}$ is the probability of the entire network to find a block, and

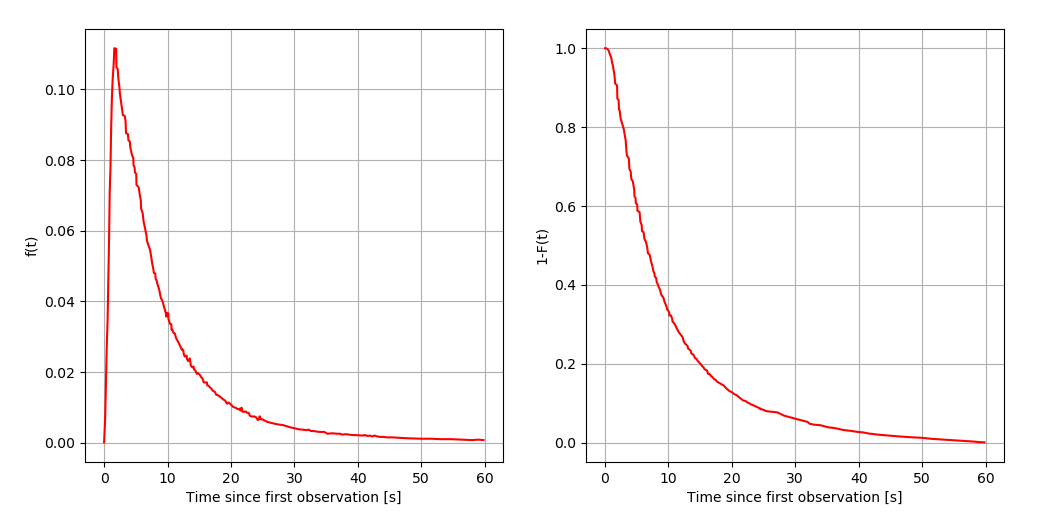

is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the rate at which a block is propagated through the network. These looked like the following back in 2012:

The graph on the left is the PDF, and the one on the right shows the percentage of the nodes that haven’t received a block after a certain amount of time. The important thing to understand is that increasing block size expands the PDF to the right, increasing the value of the integral term in the exponent, eventually increasing the forking rate. Decreasing block time does the same by increasing $P_b$. The formulas yield a value close to 1.69%, the original forking rate in 2012. That means every ~17 in 1000 blocks were orphaned.

Interestingly, forking rate in Bitcoin has decreased to almost zero in the last couple of years, owing to the biggest mining pools establishing low-latency communication channels. That means that the network now has room for a performance increase of presumably at least ~2x. The reason why it hasn’t happened until now is interesting, but out of the scope of this document.

All Proof of Work blockchains with the longest chain fork choice rule are subject to this relationship between the forking rate, block size and block time, including Ethereum 1.0. Ethereum’s current consensus bandwidth is at roughly 14.3 kbps, with an average block size of 25 kB and time of 14s. This puts Ethereum very close to Bitcoin in terms of throughput. Both finalize roughly the same number of bits per second—a news that would upset the maximalists of either blockchain.

This relationship between throughput and network would hold even if the fork choice rule were to be changed. Blockchains can’t scale by simply producing blocks faster, because they are all bottlenecked by global bandwidth. Given various non-sharded blockchains, one would observe that they perform very similarly, once their parameters and encodings are optimized. Therefore, comparing the TPS of such blockchains is moot.

If it ever becomes the case that computing power, storage or anything else other than bandwidth, are the limiting factor, we would see the same pattern—the network’s throughput would be determined by the performances of the most ubiquitious CPU or solid-state drive.

Conclusion

TPS by itself is an insufficient metric to compare two blockchains. When making a statement about differences in performance, one should include at least the following criteria:

- Use case and functionality

- Optimization for certain tasks

- Encoding efficiency

-

Performances in terms of bottlenecked resources, which may include:

- Consensus bandwidth

- Average computing power of a node

- Average storage capacity of of a node

If a single number such as TPS is nonetheless sought, these criteria should be factored into that number, proportional to the degree of their importance. Otherwise, TPS would remain only a meme.

-

See ACID properties. ↩

-

Bitcoin uses the UTXO model instead of an account based one, so that a transaction between two parties can have more than one input and one outputs. Also, CoinJoin allows users to combine their transactions for increased anonymity. ↩